Total Harmonic Distortion

Lately, I’ve been looking at harmonic distortion in circuits and was curious about the Total Harmonic Distortion, or THD, of a sine wave mixed with a square wave. That got me thinking about the math behind a square wave and how I could get an exact expression for the THD of a square wave (which is known and in countless literature [1]) and then how I could compare the result of a sine wave mixed with a square wave (both at the same fundamental).

THD of a Square Wave

First thing’s first: how can we mathematically define a square wave? By summing sine waves at each odd harmonic and properly weighting them! This is a very well known concept, as is the equation, but it’s certainly worth stating:

++ x(t)=\large\frac{4}{\pi}\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty} \large\frac{sin([2k-1]\cdot\omega_0 t)}{2k-1}++

Now, because it’s fun, let’s visualize this equation. The following animation performs a sum of k=1 to k=32. As each sine wave is summed, our transient waveform (top) approaches the behavior of an ideal square wave. The bottom plot shows the discrete fourier transform (DFT) of each summation. The blue curve corresponds to our fundamental frequency (the frequency at k=1) and the red curves are all of our harmonics. The ratio of the harmonics to the fundamental gives us our THD distortion (the actual THD equation is at the bottom of animated image).

++THD\% = \sqrt{\large\frac{\sum\limits_{k=2}^{\infty} x_{k}^{2}}{x_{1}^{2}}} ++

In order to find the THD, we need to know the components that exist at each odd harmonic and the component that exists at the fundamental. We know our fundamental is at k=1 which means:

++x_1^2 = \large\frac{16}{\pi^2}\large\frac{1}{(2\cdot 1-1)^2} = \large\frac{16}{\pi^2}++

Since the rest of the sinusoidal terms in the square wave equation are harmonics of the fundamental, we know that:

++\sum\limits_{k=2}^{\infty}x_k^2 = \sum\limits_{k=2}^{\infty}\large\frac{16}{\pi^2}\large\frac{1}{(2k-1)^2} = \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\large\frac{16}{\pi^2}\large\frac{1}{(2k-1)^2} -\large\frac{16}{\pi^2}++

By setting the initial value of ‘k’ back to one, we put the harmonic expression in a form with a known finite solution [2]:

++ \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\large\frac{1}{(2k-1)^2} = \large\frac{\pi^2}{8} ++

Plugging all of this into our THD equation above will yield a finite expression for the THD of a square wave:

++THD\% = \sqrt{\large\frac{\pi^2}{8}-1} \approx 48.3\%++

THD of a Sine Wave Mixed with a Square Wave

Now, let’s say we want to multiply our square wave with a sine wave of the form $a(t) = sin(\omega_0 t)$. It doesn’t really matter what the amplitudes are here because they are multiplied by every single harmonic, so they are cancelled in the THD ratio. When we multiply $a(t)$ with our defined $x(t)$ square wave equation defined earlier, we will get the following:

++y(t) = \frac{2}{\pi}\left[1-\frac{2}{3}cos(2\omega_0 t)-\frac{2}{15}cos(4\omega_0 t) - \frac{2}{35}cos(6\omega_0 t) - \frac{2}{63}cos(8\omega_0 t) -\ldots\right]++

That particular equation will go on to the infinith harmonic. Because of that, we can represent it as an infinite sum as follows:

++y(t) = \frac{2}{\pi}\left[1-\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\large\frac{2\cdot cos(2k\cdot\omega_0 t)}{(2k-1)(2k+1)}\right]++

Now that we have an expression, we can calculate the THD. Here, instead of our fundamental being at $\omega_0$, it is actually at DC due to the demodulation. If we ignore the $\frac{2}{\pi}$ term (since it is in front of all of the harmonics, including DC), we see that our fundamental is at ‘1’ and all of the harmonics are contained within the infinite sum. Therfore, we can say our demodulated sine wave’s THD is equivalent to the coefficient of the infinite sum of $y(t)$. Now, lucky for us, said infinite sum also has a finite solution like the square wave did [2]. Thus:

++THD\%=\sqrt{\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\large\frac{2^2}{\left((2k-1)(2k+1)\right)^2}} = 2\sqrt{\large\frac{\pi^2}{16}-\large\frac{1}{2}} \approx 68.4\%++

So the THD got worse! Well, does this actually make sense? Let’s look at it graphically:

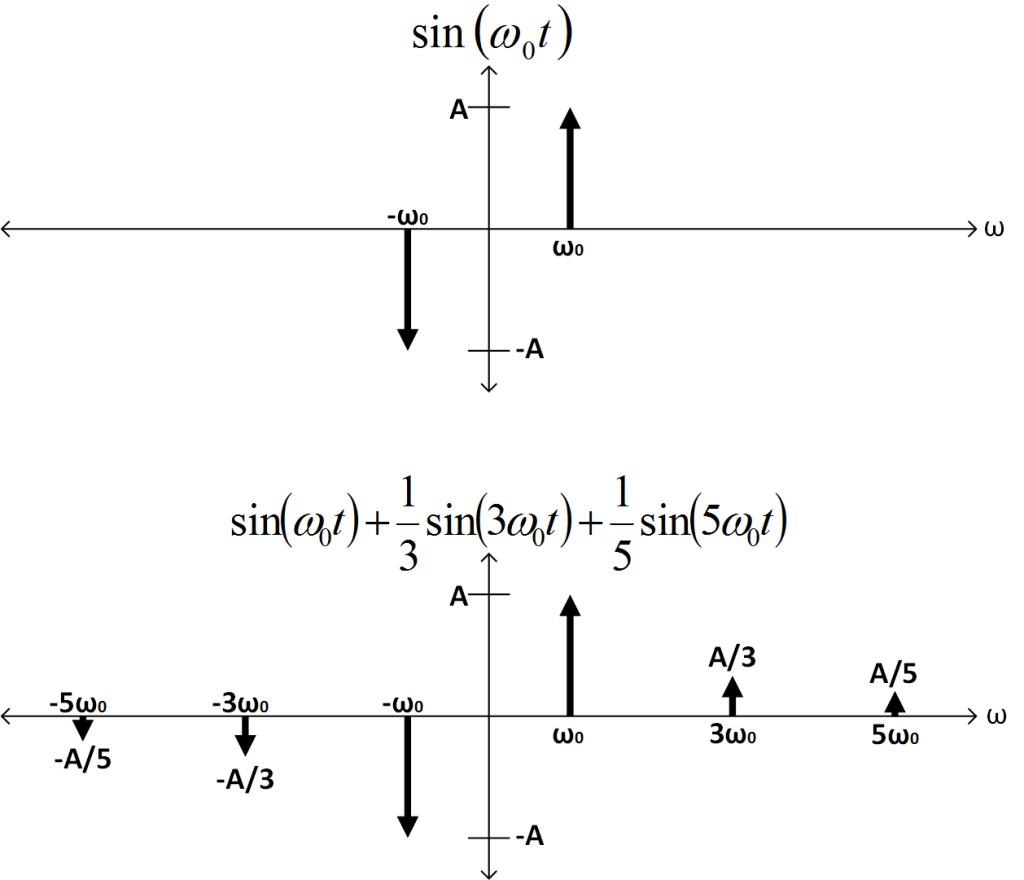

I know the fourier transform of a sine wave is $\mathcal{F}\left{sin(\omega_0 t)\right} = j\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}\delta (\omega -\omega_0)-j\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}\delta (\omega +\omega_0)$. For simplicity, instead of multiplying by a pure square-wave, let’s just say we only have the the harmonics ‘1’, ‘3’, and ‘5’. Given that, and normalizing the amplitudes to an arbitrary value of ‘A’, we can plot these signals in the frequency domain below.

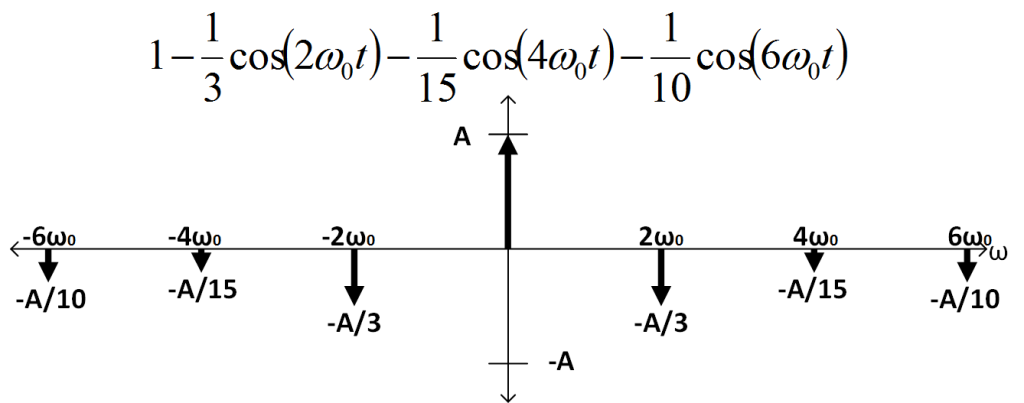

Given this, if I convolve these two waveforms (remember, multiplication in the time-domain is convolution in the frequency-domain!), I will get the following plot (the math is very straight-forward so I’ll omit it here).

Now, if we sum up the squares of the harmonics and divide by the square of the component at DC, we will have $\left(\frac{2}{10}\right)^2+\left(\frac{2}{15}\right)^2+\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2\approx 0.502 $. When we take the square root, we get $THD\% \approx 70.85%$. Which is larger than our exactly calculated value by $3.5\%$ despite only including two harmonics outside of the fundamental. As more harmonics are added into the square-wave approximation, the previous harmonic will decrease in amplitude (ie. the component at $6\omega_0$ will go from $\frac{1}{10}$ to $\frac{1}{35}$).

I just thought this was an interesting result and decided to share it; hopefully someone, somewhere learned… something!

References

[1] I. V. Blagouchine and E. Moreau, “Analytic Method for the Computation of the Total Harmonic Distortion by the Cauchy Method of Residues” in IEEE Transactions on Communications vol 59, no. 9, pp. 2478-2491 Sept. 2011. [2] D. Zwillinger, Table of Integrals, Series, and Products, 8th ed. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, 2015, pp. 10-11