Series Capacitance Error

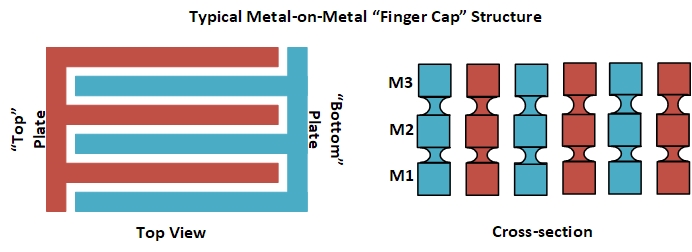

A few years ago I was working on a circuit to cancel background signals in transcapacitive fingerprint sensors. Since fingerprints features are really tiny, the capacitances were too (on the order of atto-farads. That’s $10^{-18}$!). In silicon, small capacitances can be created with multiple stacked layers of metal and can easily achieve single-digit femto-Farads (that’s $10^{-15}$). However, going below that required working outside of the foundry’s PDK which means we’re working with uncharacterized silicon structures. The solution was to connect these small capactiances in series to create even smaller capacitances (although, this comes at the cost of density since we are utilizing more silicon area to create small capacitances).

Density aside, this created an issue with parasitic capacitances since, at those dimensions, the parasitics can be a non-negligible fraction of the explicitly drawn capacitance. So I made an attempt to create a generic formula to calculate the effective capacitance for any arbitrary number of series capacitors. I failed at this.

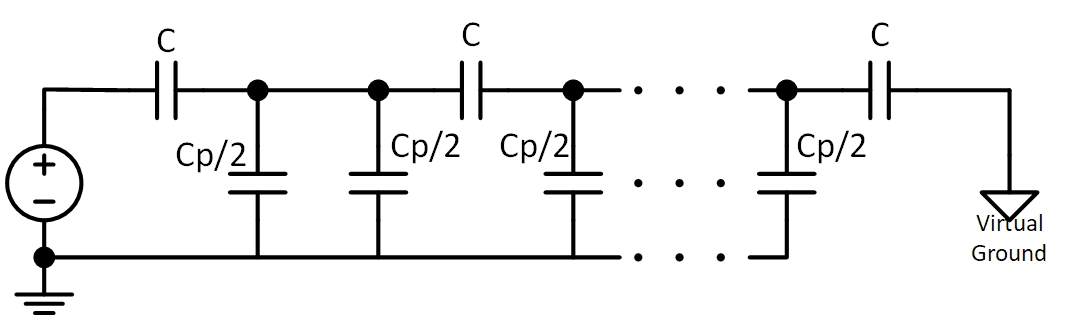

What I did come up with was a series of equations for different numbers of capacitors. For example, assuming a drawn capactiance of $C$ and a parasitic capacitance of $C_p$ I generated the following equation for three series capacitors (generic diagram for “N” caps below):

++C_{eff} = \frac{1}{3}C\left[ \frac{1}{1+\frac{4}{3}\left(\frac{C_p}{C}\right)+\frac{1}{3}\left(\frac{C_p}{C}\right)^2} \right]++

I did this for a few other variations and saw a semblance of a pattern but just couldn’t quite generate that ubiquitous general expression I wanted. Unfortunately, schedule pressure forced me to abandon the idea…until now.

For some reason I decided to dust off the ol’ notebook to take another crack at the problem and believe I solved it. My problem was treating the parasitic capacitance as a unique variable rather than as a multiple of $C$. This, in retrospect, is obvious when looking at my equation above since $C_p$ only ever appears ratiometrically with $C$. So I plugged away in octave and created the following program to generate my desired sequence:% Brute-force method of calculating effective series

% capacitance for 'N' series capacitors.

% Kevin Fronczak, 2019-09-03

NMAX = 30;

a = 0.1; % Cp/C

C = 1;

% Initial values

CA = C*a*C/(C+C+a*C);

CC = C*C/(C+C+a*C);

y(1) = 1;

for n=2:1:NMAX

y(n) = n*CC/C; % Ceff = delta * C/N so just print delta

C3 = CA + a*C;

CA = C*C3 / (CC + C3 + C);

CC = CC*C / (CC + C3 + C);

endfor

plot(y)

This is a very brute-force method to figure out the effective capacitance. But it works.

My next step was I took my hand calculations from before and looked them up on the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences to see if I had a match…and eureka! I did! The first hit was sequence A030528 which looked promising, but not quite what I was hoping for. After some further searching, I found the result for the Riordan array: A128908 which seemed to have the structure I wanted. It is a binomial function and my formula should look like this:

++C_{eff} = \frac{C}{N} \cdot \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=2}^{N} \binom{N+k-1}{2k-1}\cdot\left(\frac{C_p}{C}\right)^{k-1}}++

Alternatively, without the binomial notation:

++C_{eff} = \frac{C}{N} \cdot \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=2}^{N} \frac{(N+k-1)!}{(2k-1)!(N-k)!} \cdot \left( \frac{C_p}{C} \right)^{k-1}}++

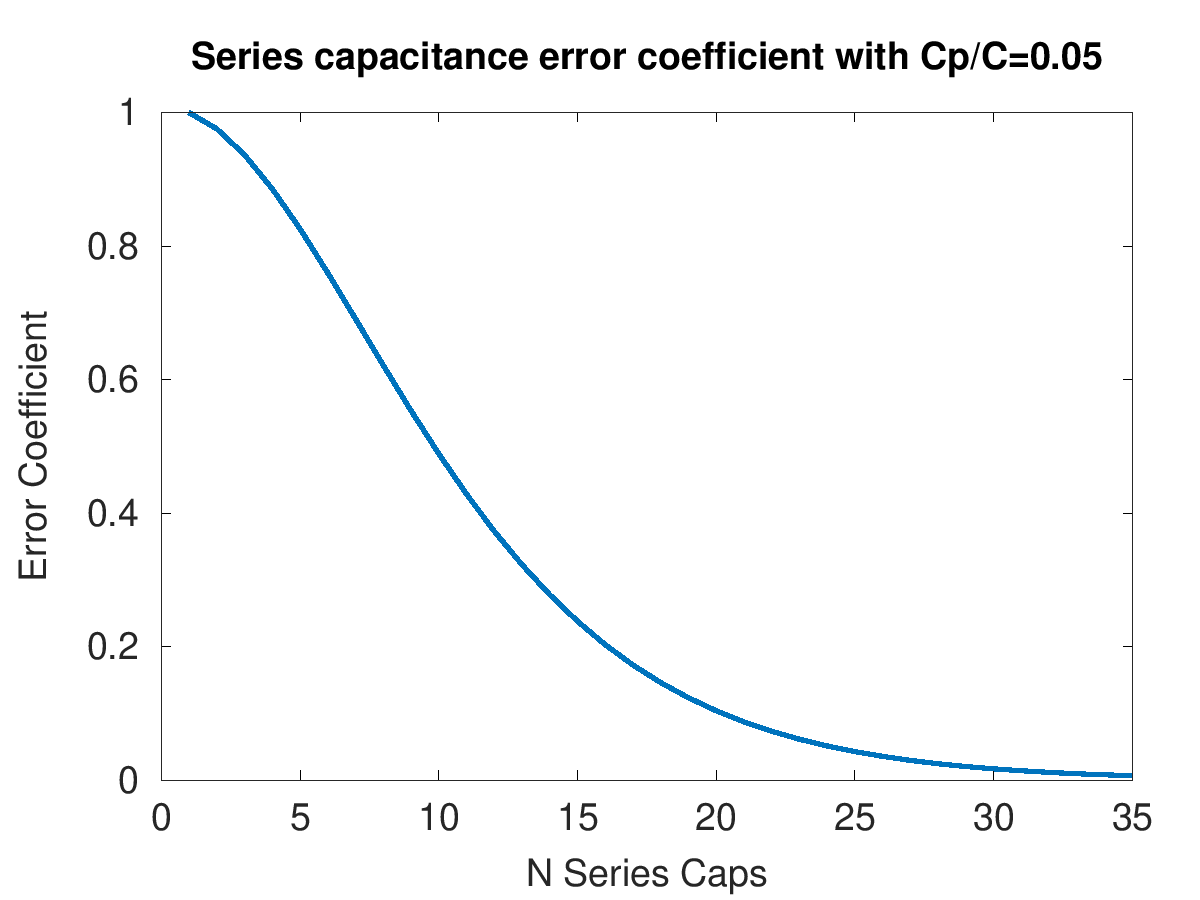

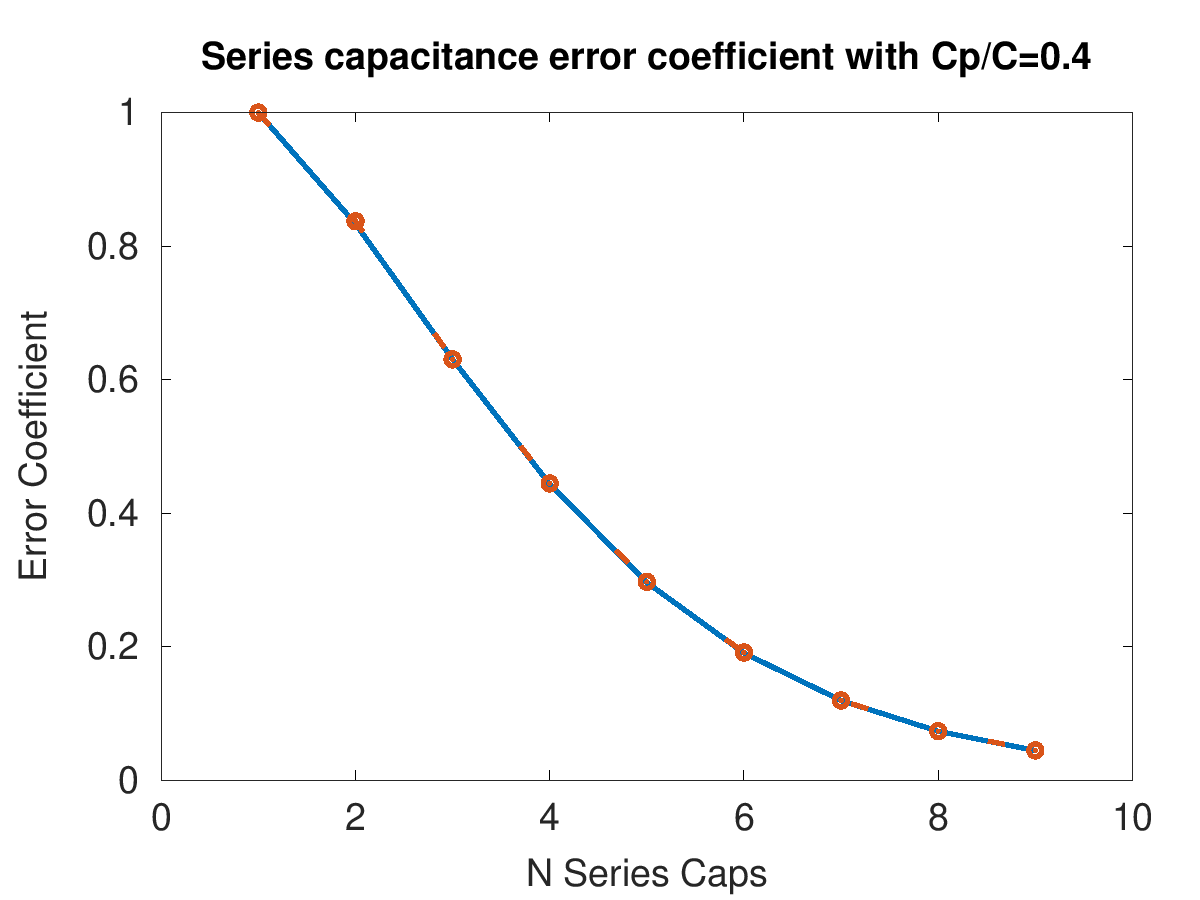

This result is not really intuitive, but it’s complete. And this makes me happy. Below is a plot of what I call the Error Coefficient ($\alpha_C$). Basically, this just condenses the equation above into

++ C_{eff} = \alpha_C \frac{C}{N} ++

Where

++\alpha_C = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=2}^{N} \binom{N+k-1}{2k-1}\cdot\left(\frac{C_p}{C}\right)^{k-1}}++

And for posterity, here’s the Octave code I used to generate this plot:% Series capacitance errors using Riordan array

% https://oeis.org/A128908'

% Kevin Fronczak, 2019-09-03

NMAX = 35;

a = 0.05; % Cp/C

C = 1;

% Initial values

y(1) = 1;

for n=2:1:NMAX

denom = 1;

for k=2:1:n

coeff = nchoosek(n+k-1, 2*k-1);

denom = denom + coeff/n * a^(k-1);

endfor

y(n) = 1/denom;

endfor

plot(y)

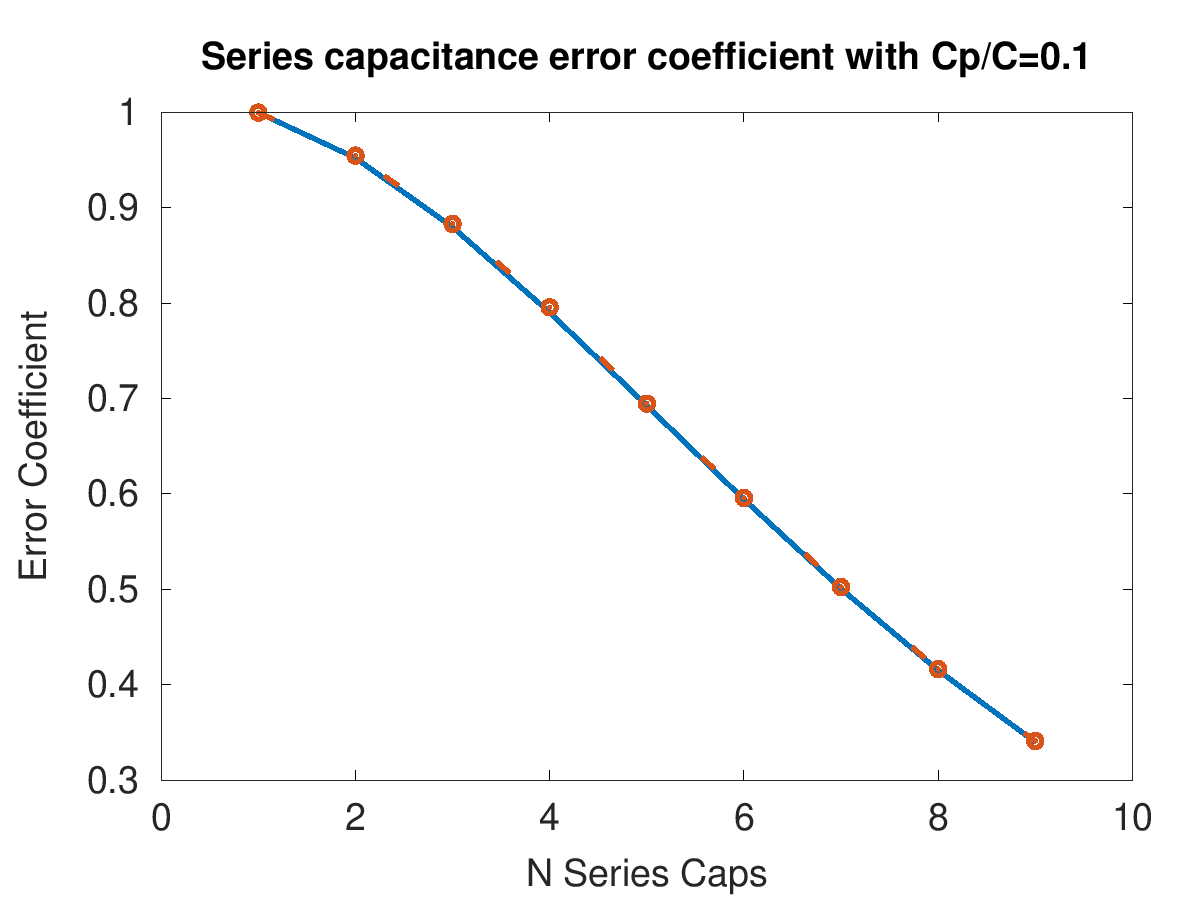

Now, how do I prove that this is actually a closed-form solution? Well…I don’t really have a formal proof. BUT! I can simulate this for a bunch of different values of $N$ and compare it to our result. I did this for two different values of $\frac{C_p}{C}$ up to $N=9$. The solid blue line indicates the calculated series, while the red circles are values from a SPICE simulation.

So…yeah. Kinda neat, eh?

Special Case $C=C_p$

There’s a pretty neat outcome when you set C=Cp, which reduces our $C_{eff}$ to the following:

++C_{eff} = \frac{C}{N}\frac{1}{1+\frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=2}^{N}\binom{N+k-1}{2k-1}} for C=C_p++

If you start to plug in various values of $N$ (and keep the result in fractional form) you start to see a familiar pattern emerge:

++\frac{C}{1} for N=1++ ++\frac{C}{3} for N=2++ ++\frac{C}{8} for N=3++ ++\frac{C}{21} for N=4++ ++\frac{C}{55} for N=5++ ++…++

Anyone even cursorily familiar with the Fibonacci sequence will notice that the denomiator of that result is just the $2N^{th}$ Fibonnaci number! So for the special case of $C=C_p$, the equation reduces to a very simple:

++ C_{eff} = \frac{C}{F_{2N}} for C=C_p++

Which is, as I mentioned previously, pretty darn neat!